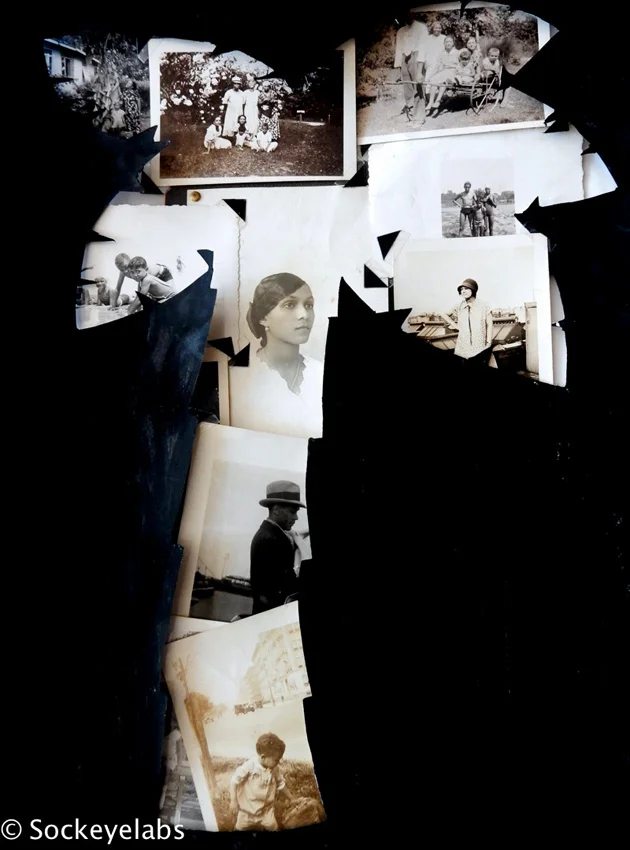

This photo-collage series documents West-Indian migration to the United States through the experience of one family - mine. The works are made from archival photos and documents, gouache, paper and digital camera. Each palm serves as a reliquary of a collective memory.

The Great Migration wasn’t limited to black descendants of the antebellum south. By 1930, almost a quarter million Caribbean natives had also made their way to the United States as a way of shedding the shackles of colonial rule. The majority set themselves up in New York City. My grandmother Flossie Salmon was one of them.

Flossie

On June 2, 1924 my newly wed grandmother Flossie George Salmon arrived at Ellis Island aboard the SS Vauban. Just a week before, she had left her native St. Lucia in the Windward Islands, to meet the majestic ocean liner in the Port of Barbados, where she took a berth in a second class cabin. She was traveling with her husband Arthur Leslie Salmon – or Feddie. He thought he was on their honeymoon. In fact, my 22 year old grandmother had every intention of remaining in New York for the rest of her life. And she did.

After declaring to immigration officials that they were neither polygamists nor anarchists, Flossie and Feddie set themselves up with relatives on West 148th Street – a neighborhood thick with Caribbean natives, whose presence in Harlem formed an elite social set in uptown Manhattan. As a group, West Indians were known to apply for and get better positions than American born migrants, and their mass arrival in the 1920s sparked antagonism between the races. West Indians thought of themselves as having a greater respect for family, education and religion, and the Salmons were no exception. Flossie had gone to St. Joseph’s Convent School and was raised a prim Catholic in a well-to-do St. Lucian family. She was not a Negro; she was St. Lucian.

Photographic portraits of the family show my father and his older, green-eyed brother in Little Lord Fauntleroy outfits and crisp sailor suits. Grandpa Feddie, a clerk at the Navy Yard in Brooklyn wears a bowler hat and overcoat, and Flossie is in the latest flapper fashion rocking something she surely picked up from her early jobs in the garment district.

By the time her sons were growing up, Flossie and Feddie were homeowners in Sugar Hill, and she was a celebrated, self-employed caterer planning banquets for mostly Jewish housewives in Forest Hills and Stamford, CT. She made cakes that were lavishly decorated, multi-tiered confections, and she carved giant bowls out of ice, filling them with sweet punches.

“We want to thank you and your staff for the splendid party you set up for us,” Mrs. Rhoda Zimmerman wrote after one such affair. “Everyone was impressed!”.

My father and his brother went to parochial schools where they were invariably the lone dark faces. A high school class picture shows my father smiling at a retreat for Bishop DuBois boys in April 1950. At 18, he’s one of a handful of tawny faces in a pale crowd of 100 – an unusual sight for that time. When I consider what it must have been like for him to navigate that divide, I’m comforted to remember that this was his strength. He was a gregarious young man comfortable in any setting, who charmed his peers with a captivating smile and affable manner. As I examine my own parallel immersion, I feel a a heavy dose of his social DNA.

Even though she never went back to live there, Flossie never abandoned her ties to St. Lucia. While collecting U.S. war bonds, she still kept in close touch with her mother Esther back home, to whom she would send pound cakes, as well as boxes of trinkets like soap dishes, powder puffs and coin purses; and gold buttons, fake pearls and embroidered fabric which her mother would make into decorative table linens to sell to the locals. In return, Esther would send back cases of whisky for Flossie’s cranky older sister Hennie who had come to live with her when my father left for college and Feddie moved out.

By 1950 most of Flossie’s eleven George siblings (ten in total) had left St. Lucia and moved to New York, mostly settling in Bedford-Suyvesant, Brooklyn – a post-war West Indian enclave – where there were sturdy brownstones and easy access to Manhattan by the A train. Flossie, the tireless entertainer - and close studier of the Larousse Gastronomique - had parties for the extended George clan as often as each brother or sister got married or had children. That was often. There was constant revelry at 463 West 153rd Street, where on special occasions crisp, golden codfish cakes were served on doilied platters alonsgside flaky meat patties and fried plantains. For dinner, traditional St. Lucian dishes like Callalloo soup, rice and peas, Green fig and fish, and oxtail stew were center-stage on her glass-topped dining room table. Everyone served themselves buffet style, some eating while standing up and swaying to the latest Calypso rhythm.

For dessert there was a choice of lemon meringue or pineapple pie. By evening’s end there were, without exception, two brothers and Hennie passed out in the kitchen from too much Barbadian rum.

This was the scene my mother walked in on when she met my father in 1954. The enthusiasm for life at my grandmother’s house was intoxicating. The confidence this family exuded, the lightness and sense of fun that permeated that place was down right exotic compared to the drab apartments and dull home life she’d been used to with her own mother and father whose ancestors came up from the south. It was absolutely necessary that she marry into this family because it was an impressive step up from her ordinary life in Harlem. She’d never meet anyone with a clan like this, so she got to working on this very thing she desired.

And, indeed, she got married and had a wedding party in that very house, in that very George family way. But it wasn’t long before she found out that all that magic wasn’t hers to own. Because, in their eyes, and particularly in the patronizing eyes of the West Indian matriarch Flossie, she was just a common American Negro, charting her own migration.